No winner in Washington's chip war against Huawei

Semiconductor and smartphone industries worldwide, including those in the United States, are bracing for extreme disruptions after Washington recently tightened its restrictions on Chinese tech giant Huawei's ability to obtain critical components, most significantly, chips.

On Aug. 17, the U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) announced its decision to require foreign manufacturers using U.S. technology to get a license if they plan to sell semiconductors to Huawei.

Intended to curb Huawei's growth, the new rule will send out a chilling wave across global supply chains, analysts say.

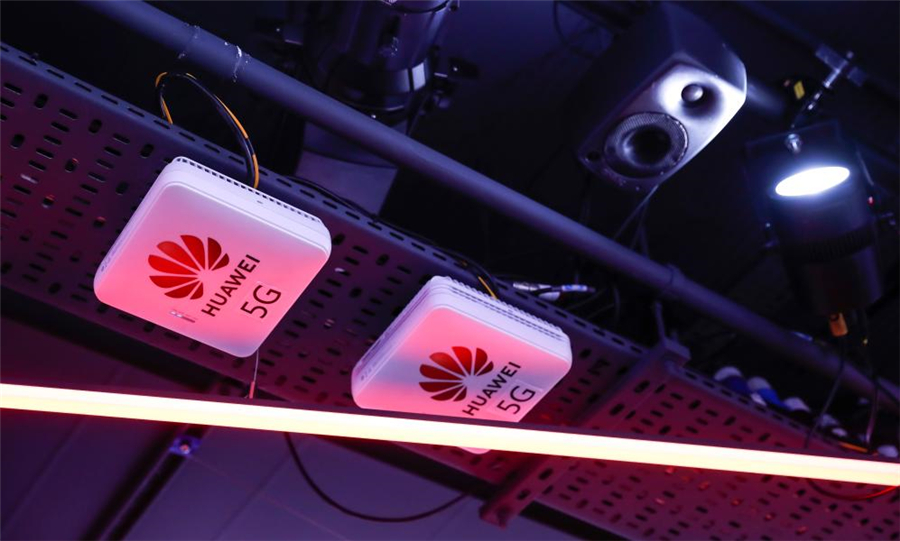

Photo taken on Jan. 28, 2020 shows Huawei 5G equipment at Huawei 5G Innovation and Experience Center in London, Britain. (Xinhua/Han Yan)

ESCALATING SUPPRESSION

Last year, the DOC essentially banned U.S. firms from selling Huawei chips made in the United States. In May, the DOC amended a rule to target Huawei's acquisition of semiconductors that are the direct product of certain U.S. software and technology.

Though the May restriction severed Huawei's supply of custom-made chips, the Chinese company could nonetheless buy off-the-shelf chips designed by a third party.

However, with the latest move, Washington "further restricts Huawei from obtaining foreign made chips developed or produced from U.S. software or technology to the same degree as comparable U.S. chips," the U.S. department said on its website.

"The move is the latest and potentially most serious effort by the U.S. government to choke off the company's ability to obtain advanced semiconductors for all of its business lines," the CNBC quoted Eurasia Group, a political risk consultancy, as saying.

In response, Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian told a press briefing earlier this month that the United States has been abusing the concepts of national security and state power to impose various restrictions on Chinese companies, which constitutes "a blatant hegemonic act."

Behind the move, observers say it is the sole superpower's chip dominance that gives Washington a "powerful weapon" against the Chinese company. Geoff Blaber from the research and advisory company CCS Insight told the Nikkei Asian Review that while the semiconductor industry is "global in nature," its foundation "is very, very heavily based on" the United States.

"The leading players in chip design software are all American companies," according to a report by the Nikkei Asian Review last week. "Chip fabrication, like design, relies heavily on U.S.-made chipmaking and chip testing equipment."

COUNTERPRODUCTIVE RULE

Shortly after Washington's decision, the country's Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), which represents 95 percent of the U.S. semiconductor industry, was surprised and concerned.

"We are still reviewing the rule, but these broad restrictions on commercial chip sales will bring significant disruption to the U.S. semiconductor industry," SIA President and CEO John Neuffer said in a statement on the association's official website.

"We reiterate our view that sales of non-sensitive, commercial products to China drive semiconductor research and innovation here in the U.S., which is critical to America's economic strength and national security," the statement added.

With the termination of sales to Huawei, which bought 19 billion U.S. dollars in components from U.S. firms last year, "technology bosses fret that their government's actions will drive investment away from them to rivals in other countries," the Economist magazine reported this month.

Meanwhile, according to a March report by the Boston Consulting Group, over the next three to five years, U.S. companies could lose 18 percentage points of global share and 37 percent of their revenues if the United States "completely bans semiconductor companies from selling to Chinese customers, effectively causing a technology decoupling from China."

These drops in revenue, the analysis warned, would "inevitably lead U.S. semiconductor companies to make severe cuts in R&D and capital expenditures, resulting in the loss of 15,000 to 40,000 highly skilled direct jobs in the U.S. semiconductor industry."

Photo taken on March 5, 2020 shows Huawei's flagship store in Paris, France. (Xinhua/Gao Jing)

CHILLING EFFECT

Omu Kakujaha-Matundu, a lecturer and economist from the University of Namibia, told Xinhua that Washington's Huawei ban is not in line with international trade practices of fair market access and is also detrimental to the introduction of technological advancement anywhere in the world.

"This now stops (U.S. chipmakers) Nvidia, Intel, everyone, and they were not impacted before," an industry expert told the Financial Times, adding that the tighter restrictions would affect billions of dollars in business across the sector.

Among the first batch of victims, the Taiwanese chipmaker MediaTek's share price plunged by 10 percent on the news. Shares in Japanese electronics titan Sony also fell more than 1 percent on Aug. 18.

Over the long term, as The Wall Street Journal editors wrote in June, other countries may face a more difficult choice. "Foundries in Southeast Asia that rely on Huawei's business may resent being subject to extraterritorial U.S. rules, and one risk is that those governments are pushed closer to Beijing. Huawei will also accelerate its efforts to make chips using its own know-how and take a faster technological leap."

Similarly, noting that "Huawei is determined to succeed and has considerable research and development resources," The South China Morning Post said in an editorial on Saturday that instead of seeing off competition, the U.S. administration is "speeding up Chinese self-reliance."

The chip ban, as David P. Goldman, a columnist for news platform Asia Times said, gives the world "an enormous incentive to circumvent" the United States, raising the risk that the United States rather than China "will be left without a chair when the music stops."